Video games and attention: Gaming enhances some attention skills, and hinders others

© 2021 Gwen Dewar, all rights reserved

What’s the connection between video games and attention? Do video games cause attention problems? Or do they help children focus? It seems that both are true.

Certain “action” video games can enhance a variety of visual attention skills, and they may even help children with reading disabilities. But there’s a downside. Action gaming may also hinder “proactive control,” a kind of attention that is patient, careful, and sustained.

Here are the details.

Unpacking the concept of attention

What do we mean when we say someone is “paying attention?” What do we mean when we say someone has “good visual attention skills”?

Attention is about focusing your mental resources on something, and avoiding distractions. But that’s a pretty vague description, isn’t it? If we unpack the concept of attention, we find that it includes a number of distinct abilities.

For instance, imagine you are a lifeguard, standing on a tower overlooking a crowded shore. You see lots of people in the water, but it’s your job to look out for other things too. And then you see it — the dorsal fin of a shark.

It disappears in less than a second, but you were able to spot it and note its location. If I ask you to point to the area where that dorsal fin appeared, you are pretty accurate.

That’s one kind of attention skill — being quick to notice and locate select objects that appear briefly in your field of view. Here are a couple more:

You are visiting a busy amusement park with several children. Suddenly they dash off, each child moving in a different direction. It’s hard to distinguish them in the crowd, but you manage to keep sight of them. Psychologists call this “multiple object tracking.”

You’re back on the beach, a lifeguard scanning the water for sharks and swimmers in trouble. But you have to keep an eye on the land, too, because beachgoers sometimes engage in dangerous or illegal behavior. When needed, you can quickly snap your focus from one thing to the next. This skill is related to what psychologists call “attention switching” or “task switching.”

How do these abilities relate to video games?

All three concern visual attention, and video games are a visual medium. But clearly, there’s more to it. In many video games, these are crucial skills for success.

- Players are required to monitor a field of view that is crowded with distractors, and quickly locate special targets when they suddenly appear.

- Players must try to keep track of multiple objects simultaneously.

- Players need to be capable of rapid shifts of focus — switching their attention from one urgent task to the next.

This is especially true for “shooter” video games — action games where the goal is for the player to defeat enemies with long-range weapons.

So perhaps it shouldn’t surprise us: People who play “shooter” action video games tend to have superior attention skills relating to field of view, multiple object tracking, and task-switching.

It’s been documented in adults (e.g., Bavelier and Greene 2019; Bediou et al 2018; Qiu et al 2018; Wu and Spence, 2013). It’s been documented in children too.

For example, back in 2010, Mathew Dye and Daphne Bavelier recruited 114 school kids between the ages of 7 and 17.

Among these children, approximately one-third had prior experience playing “shooter” video games. The remaining two thirds lacked this experience. And it made a difference.

The kids who had a history of playing “shooter” video games were better at noticing and locating objects in their field of view. They also showed an enhanced ability to pay attention to multiple objects simultaneously.

Of course, these are merely correlations. We can’t assume from such studies that playing video games causes improvements in visual attention.

But researchers have also performed controlled experiments.

They’ve recruited volunteers without gaming experience, and then randomly assigned them to play either “shooter” video games or “non-shooter” video games. The outcomes?

Across a variety of studies, people assigned to play fast-paced “shooter” video games have improved their performance on “field of view” tasks.

They’ve also improved their ability to track multiple objects, and to rapidly shift attention between tasks (Bediou et al 2018; Bavelier and Green 2019; West et al 2020; Vedechkina and Borgonovi 2021).

So the consensus among researchers is that we can enhance certain visual attention skills by playing action video games (Bediou et al 2018).

Can video games boost attention in ways that benefit children academically?

One fascinating possibility is that gaming might help children improve their reading skills.

In particular, studies suggest that children with dyslexia might learn to read faster.

If this sounds far-fetched, consider that people with dyslexia tend to have a hard time switching their attention from visual to auditory stimuli. This makes the standard approach to reading — seeing a letter and imagining the sound it makes — very difficult.

As we’ve noted, action video games appear to boost players’ attention-switching or task-switching skills. So perhaps gaming could benefit children with dyslexia (Harrar et al 2014).

Where’s the evidence?

Much of it comes from the work of Sandro Franceschini and his colleagues. They have used commercially-available, age-appropriate action games (mini games from the E-rated title, “Rayman’s Raving Rabbids”) to see if action gaming can improve reading speed in dyslexic kids.

In one study, they recruited 20 Italian children (10 year olds) with dyslexia. They tested the kids’ attention skills and reading abilities, and then they asked the children to play video games in daily sessions for two weeks.

Half the kids were randomly assigned to play only “action” games — games that include “shooter” mechanics (e.g., shooting carrot juice at cartoon rabbits), and a variety of unpredictable, fast-moving objects in the player’s field of view.

The other half were randomly assigned to play only games that lacked these features.

After video game training, the researchers re-tested the children’s attention skills and reading abilities.

Were there any changes? Yes. And it was the kids who played action video games who showed the biggest improvements.

Not only did they perform better on attention tests. They also improved their reading speed — without any loss of reading comprehension.

In fact, their gains in reading exceeded the amount of spontaneous, developmental improvement that kids ordinarily make over the course of a year (Franceschini et al 2013).

It was a single, small study, so we shouldn’t jump to conclusions. In fact, when researchers in a different lab performed a similar experiment in Polish-speaking children, they failed to replicate the effect (Łuniewska et al 2018).

However, in subsequent studies, Franceschini and his colleagues have reported more such successes, in both Italian-speaking children and English-speaking children (Franceschini et al 2017; Franceschini and Bertoni 2019; Bertoni et al 2021).

And these experiments offer hints as to why some kids might fail to benefit from playing action video games: Research suggests that it’s essential that kids develop video game expertise.

In two studies, only kids who became proficient at action video games went on to show reading improvements (Franceschini and Bertoni 2019; Bertoni et al 2021).

Moreover, there are indications that a child’s age matters. If you start playing video games at an earlier age, you may be more likely to develop enhanced task-switching skills.

In a study of 134 university students living in Singapore, researchers compared three groups:

- students who had begun playing video games before the age of 12

- students who had begun playing video games after the age of 12; and

- students who had never played video games.

All three groups came from similar socioeconomic backgrounds. They scored similarly on a test of cognitive ability. But what about task-switching?

The researchers tested the participants’ task-switching abilities, and they found that the “early start” group had the best task-switching abilities — better than both the “late start” video gamers and the folks who had never played video games at all.

By contrast, the “late start” group didn’t display any advantage over non-gamers. Their task-switching skills were not significantly different (Hartono et al 2016).

In summary, there is convincing evidence that action video games can benefit certain attention skills.

In addition, it’s possible that action video games could help kids with dyslexia, but this research is mixed, and the details are still emerging.

What about the downside? Is there any evidence that video games can cause attention problems?

Laboratory studies suggest that action video gaming might worsen the type of attention that is careful and sustained.

We’ve talked about several aspects of attention so far — locating objects in your field of view, tracking multiple objects, and task-switching. But there are other ways to measure attention.

Imagine, for example, these scenarios.

- You are driving on a road when a deer darts out in front of you. You immediately react, and avoid a collision.

- You are driving on a similar road, but this time you’re given a heads-up. You see a sign warning you that animal crossings are common. As a result, you become more vigilant, and when a deer suddenly dashes into view, you react even faster than usual.

In both scenarios, you are paying attention. But in the first example, you aren’t engaging special attention resources until after the animal appears. Psychologists call this “reactive control.”

By contrast, in the second example you’ve “turned on” special attention resources in anticipation of something happening. You receive information about what to expect, and you use this information to actively guide your future responses.

It’s what psychologists call “proactive cognitive control,” and it’s particularly relevant to our everyday definition of “good attention skills.” You read clues, and use them to become more careful. You remain watchful for specific events, even if nothing terribly exciting is happening right now.

So how does action video game playing impact “proactive cognitive control”? It appears to have a negative effect.

To see what I mean, consider a recent experiment conducted by Robert West and his colleagues on college students living in Iowa.

West’s team recruited 77 students, none of whom played video games excessively. (To participate in this study, you couldn’t be in the habit of playing video games more than 5 hours per week.)

The researchers began by measuring the students’ baseline attention skills. Students performed a “field of view” task. They also took tests that measured their reactive and proactive control.

Then came the treatment phase. Each student was randomly assigned to one of four different groups:

- The action video game group, in which students played a fast-paced, first-person shooter game called “Unreal Tournament”;

- The real-time strategy video game group, in which students played a game (“Faster Than Light”) that lacks the rapid pace and first person shooter mechanics of “Unreal Tournament”;

- The simulation video game group, in which students played a non-action video game, “The Sims”; and

- The no-gaming control group, in which students played no video games.

Students assigned to the video game groups (action, strategy, or simulation) participated in 10 gaming sessions over the next few weeks, racking up about 9 hours total game time.

Students assigned to the non-gaming group went about their lives as normal, with no scheduled gaming sessions.

When the treatment phase was complete, researchers re-tested the students. What happened?

None of the gaming groups experienced improvements in reactive control. But on the other measures, kids who had played the action game stood out.

Consistent with previous studies, the action gamers came away with the biggest improvements on the field-of-view task.

But they were also the only group to experience a decrease proactive cognitive control. Nine hours of action gaming seems to have made their proactive control skills worse (West et al 2020).

Is there any other research to back this up?

Yes. For example, back in 2010, Kira Bailey and her colleagues compared the behavior and brain activity of two different groups of young men:

- a group that was in the habit of playing video games more than 40 hours per week, and

- a group that played video games less than 2 hours per week.

There was no experimental manipulation in this case. Bailey’s team simply wanted to know if people’s pre-existing video game habits were correlated with differences in attention.

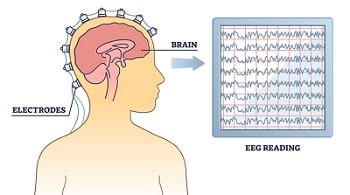

So they asked the young men to perform tasks that tapped both reactive control and proactive control. At the same time, they measured the men’s brain activity by recording brain ERPs, or event-related potentials.

What did they find? The two groups performed similarly on tasks requiring reactive control. Their brain activity looked the same too.

But when it came to proactive control, there was a distinct difference.

The “high volume” (40+ hours per week) gamers were outperformed by “low volume” gamers, and their brain activity showed less evidence of paying attention during the brief, “wait and see” intervals of the tests (Bailey et al 2010).

So are gamers at greater risk of having problems with patient, sustained attention? The kind of attention that’s important in the classroom?

Maybe.

In laboratory tests of sustained attention, adolescents who play action video games tend to perform worse (Trisolini et al 2018; Petillit et al 2020). They were good at the instantaneous, reactive control stuff — avoiding a collision when the deer darts out onto the road. They weren’t so good at tasks that require sustained vigilance.

Moreover, there is evidence that time spent playing video games is linked with attention problems at school.

Edward Swing and his colleagues tracked more than 1300 American children for about 13 months (Swing et al 2010).

They asked the kids, in grades 3-5, to keep track of how much time they spent playing video games. These tallies were cross-checked against their parents’ reports.

The researchers also asked teachers to evaluate each child’s attention skills at 4 different time points during the 13-month study.

When Swing’s team analyzed the results, they found a weak, but statistically significant, link between video games and teacher-reported attention problems. And the pattern was consistent with the idea that playing video games causes attention problems.

Why? Because kids who played more at the beginning of the study experienced increased attention problems at the end. This was true even after controlling for prior student attention problems. Teachers said the kids got worse over time.

What’s the takeaway?

The takeaway is that attention isn’t any one thing. It’s a set of abilities, and it’s possible to be better at some of these abilities and worse at others.

As I write this in 2021, we have pretty convincing evidence — experimental evidence — that you can improve certain visual attention skills by playing action video games.

As I note elsewhere, it also appears that video game training can help you develop certain spatial skills.

And it all makes sense.

These games reward players who can quickly detect movement in their field of view; who can track multiple, fast-moving objects; who can rapidly switch attention between different tasks.

Playing these games provides practice, and people learn from practice. If we ask trainees to perform tasks that are similar to those they’ve mastered in a video game, they will likely be able to transfer their skills to the non-gaming context.

But of course not every aspect of life resembles an action video game. There are very important attention skills that have little to do with tracking fast-moving objects. They depend instead on remaining focused during times of relative quiet or calm. And this, perhaps, is where action video games can hinder our performance.

How serious are the negative effects of video games on attention? That’s an important question, and I don’t think we have enough information to answer it.

In the study led by Edward Swing, the correlation between video games and attention problems was quite modest. But in that study, the researchers didn’t drill down — they didn’t find out what kinds of video games children were actually playing. So the analysis is lumping together a wide range of games — including educational games, strategy games, simulation games — that may have had very different effects.

The experiment by Robert West’s team is more targeted, but it doesn’t tell us how game-induced detriments in proactive control might affect a child’s performance in the classroom.

So we really do need more research to sort this out. Meanwhile, we can take a level-headed, nuanced approach to action video games.

It’s not hype to say that action gaming can improve visual attention skills, and these skills have value in the real world.

But this doesn’t mean that action video games have only beneficial effects, or that action gaming is a good therapy for improving sustained attention in the classroom. As with most things in life, action gaming comes with a downside. We need to be aware of that there are both costs and benefits.

More reading on the effects of video games

Interested in the effects of video games on spatial skills? See my article about the beneficial effects of video games on the visual mind.

In addition, check out these Parenting Science articles:

References: Video games and attention

Bailey K, West R, and Anderson CA. 2010. A negative association between video game experience and proactive cognitive control. Psychophysiology. 47(1):34-42.

Bediou B, Adams DM, Mayer RE, Tipton E, Green CS, Bavelier D. 2018. Meta-analysis of action video game impact on perceptual, attentional, and cognitive skills. Psychol Bull. 144(1):77-110.

Bertoni S, Franceschini S, Puccio G, Mancarella M, Gori S, Facoetti A. 2021. Action Video Games Enhance Attentional Control and Phonological Decoding in Children with Developmental Dyslexia. Brain Sci. 11(2):171.

Dale G, Joessel A, Bavelier D, and Green CS. A new look at the cognitive neuroscience of video game play. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1464(1):192-203.

Dye MWG, Green CS, and Bavelier D. 2009. The development of attention skills in action video game players. Neuropsychologia, 47, 1780-1789.

Franceschini S and Bertoni S. 2019. Improving action video games abilities increases the phonological decoding speed and phonological short-term memory in children with developmental dyslexia. Neuropsychologia. 130:100-106.

Franceschini S, Gori S, Ruffino M, Viola S, Molteni M, and Facoetti A. 2013. Action Video Games Make Dyslexic Children Read Better. Current Biology.

Franceschini S, Trevisan P, Ronconi L, Bertoni S, Colmar S, Double K, Facoetti A, Gori S. 2017. Action video games improve reading abilities and visual-to-auditory attentional shifting in English-speaking children with dyslexia. Sci Rep. 7(1):5863.

Harrar V, Tammam J, Pérez-Bellido A, Pitt A, Stein J, Spence C. Multisensory Integration and Attention in Developmental Dyslexia. Curr Biol. 2014 Feb 11. pii: S0960-9822(14)00062-1.

Hartanto A, Toh WX, Yang H. 2016. Age matters: The effect of onset age of video game play on task-switching abilities. Atten Percept Psychophys. 78(4):1125-36.

Petilli MA, Rinaldi L, Trisolini DC, Girelli L, Vecchio LP, Daini R. 2020. How difficult is it for adolescents to maintain attention? The differential effects of video games and sports. Q J Exp Psychol (Hove). 73(6):968-982.

Steenbergen L, Sellaro R, Stock AK, Beste C, Colzato LS. 2015. Action Video Gaming and Cognitive Control: Playing First Person Shooter Games Is Associated with Improved Action Cascading but Not Inhibition. PLoS One. 10(12):e0144364.

Swing EL, Gentile DA, Anderson CA, and Walsh DA. 2010. Television and video game exposure and the development of attention problems. Pediatrics. 126(2):214-21.

Trisolini DC, Petilli MA, Daini R. 2018. Is action video gaming related to sustained attention of adolescents? Q J Exp Psychol (Hove). 71(5):1033-1039.

West R, Swing EL, Anderson CA, Prot S. 2020. The Contrasting Effects of an Action Video Game on Visuo-Spatial Processing and Proactive Cognitive Control. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17(14):5160.

Content of “Video games and attention” last modified 6/2021

Portions of this text are derived from an older article by the same author.

title image of young child and father by Dusan Petkovic / shutterstock

image of shark by ap-images / istock

image of crowded amusement park by luvemakphoto / istock

image of beach by luvemak / istock

image of two boys playing video game cropped from a photo by monkeybusinessimages / istock

illustration of EEG and ERPs cropped from an image by by VectorMine / istock