The social world of newborns: Why babies are born to learn from our sensitive, loving care

© 2021 Gwen Dewar, Ph.D., all rights reserved

Yes, newborns spend most of their time sleeping and eating. But babies are more than mere survival machines. At birth, they are primed and ready for social input, and our loving care has profound effects on their development.

Decades ago, people underestimated newborns. People assumed that young infants were empty-headed, passive lumps. Babies didn’t really have minds—not yet—and they certainly didn’t respond to social stimuli.

Today we know better.

Months before birth, a baby can smell and hear. Babies can also touch themselves in the womb, feeling the contours of their own faces.

These sensory experiences provide a developing fetus with crucial clues about the social world. And — after birth — babies appear to be capable of rapid learning about their environment.

So newborns aren’t blank slates, and the people who care for newborns are more than diaper-changers.

Here are some examples of what newborn babies can do — the social abilities that infants display within days (and sometimes hours) of birth.

Can newborns recognize their mother’s voices?

Yes, newborns recognize their mothers’ voices — and more.

By the time an infant has been born, he or she has “overheard” quite a bit of speech, especially maternal speech. It’s muffled, obviously, but babies can detect some of the rhythms and tones of speech, and this permits them to make some pretty impressive distinctions.

For example, newborns can tell the difference between their mother’s voice and the voice of a female stranger.

They can also discriminate between the sounds of different languages, and they may show a preference for listening to their native language.

How do we know this stuff?

Researchers have used clever techniques that allow newborn babies to “vote.”

In a classic experimental design, babies are provided with pacifiers to suck on, and researchers respond to an infant’s fast-paced sucking by continuing to play an audio recording. If the baby suddenly stops sucking? The researchers abruptly stop the playback.

The newborns are quick to catch on, and soon they use their power of choice to take charge of the experimental “playlist.” Given the choice between listening to mom’s voice and listening to the voice of a stranger, newborns have voted for mom (DeCasper and Fifer 1980).

What about language preferences? Newborns have those, too.

In an experiment on 4-day old infants, researchers presented French babies with recordings of a bilingual speaker telling the same story—once in French, and once in Russian. The babies—who had “overheard” French in the womb—showed a clear preference for the French version of the story (Mehler et al 1987).

What other sounds do newborns prefer?

Studies show that newborns prefer the sound of voices — including monkey voices — to synthetic sounds (Vouloumanos et al 2010). It’s a helpful bias to have if you are trying to learn language. Pay more attention to noises that come from a primate vocal tract.

But newborns show an additional bias that’s even more helpful. They like to listen to a special style of talking that researchers call “infant-directed speech.”

This is a style of speech that adults frequently adopt when addressing a baby. We begin to speak more slowly. Our tone becomes more varied, exaggerated, and musical. We tend to emphasize certain words when we talk, and repeat these words over and over again.

As I explain elsewhere, it’s way of talking that makes it easier for babies to interpret our emotions. It may also help babies learn to talk. So it’s pretty interesting that babies show a preference for “infant-directed speech” so early in life. Researchers have documented the bias in babies who were just 2 days old (Cooper and Aslin 1990).

What about faces? Can newborns make out faces?

In experiments, new infants have shown a preference for looking at faces and face-like stimuli (e.g., Batki et al 2000; Turati et al 2002).

Can newborns recognize faces? Can they identify their mothers’ faces?

As I explain my article about newborn sensory abilities, young babies can’t see very well. Their vision is blurry.

Yet it appears that newborns learn to recognize certain faces very quickly.

In one study, researchers presented babies with video playbacks of women’s faces (Bushnell et al 1989). The infants—who were between 12 and 36 hours old—showed a clear preference for watching their mothers’ faces (as opposed to the face of another woman).

Other studies have replicated these results, and offer insight into the clues that babies use to tell people apart. They are probably noticing differences in face shape, hairstyle, and hair color (Pascalis et al 1994).

Can newborns read faces?

That might be too difficult for them, though at least one study suggests newborns can tell certain facial expressions apart. Given a choice between fearful and smiling faces, newborns looked longer at the smiling faces (Farroni et al 2007).

In addition, there’s resason to think that newborns pay attention to the direction of our gaze.

Show a newborn two versions of the same face — one that is staring off to the side, and another that appears to be looking directly at the infant — and the baby will look longer at the version making eye contact (Farroni et al 2002; Guellaï and Streri 2011).

The effect may depend on more than just visual cues. In one experiment, researchers found that babies formed these preferences only for individuals who had both made eye contact and addressed them with infant-directed speech (Guellaï et al 2015).

But regardless, it appears that newborns are sensitive to eye contact. And they are quite good at distinguishing direct gaze from a near-miss.

In a study of 32 newborns, researchers presented babies with video recordings of strangers. All video clips featured a close-up of an unfamiliar woman’s face, and in each case, the woman was talking — communicating with infant-directed speech.

But in half the clips, the woman’s gaze was trained directly at the camera. In the other half, the woman adopted a “faraway” gaze: She was looking at something just above the camera.

As you can see from these examples — reprinted here with permission of the study’s authors — the difference wasn’t super-obvious.

But the babies noticed that “faraway” look. They looked longer at faces under the direct gaze condition (Guellaï et al 2020).

There is also evidence that newborns pay attention to the overall expressiveness of faces.

Do newborns prefer faces that are emotionally responsive? Lively?

One method for testing this is called the “Still-Face Paradigm,” and it works like this:

An adult — typically the caregiver — is asked to interact in a normal way with the baby. Then the adult suddenly adopts a neutral facial expression.

The baby’s reactions are recorded and analyzed.

Still-Face experiments conducted in Switzerland have shown babies as young as 6 weeks “reliably decreased their visual attention and positive affect” [emotion] when their adult partners’ faces go blank (Bertin and Striano 2006).

A study of 2-month-old babies in Taiwan obtained similar results (Hsu and Jeng 2008).

And in Scotland, researchers have detected signs of distress in babies less than 4 days old (Nagy et al 2008; Nagy et al 2017).

Can newborns imitate us?

That isn’t clear, but newborns definitely react to our facial expressions and gestures.

Back in 1983, Andrew Meltzoff and Keith Moore performed a landmark experiment. They presented babies (ranging in age from 1 hour to 3 days old) with video playbacks of a stranger making faces.

- In one condition, the stranger stuck out his tongue.

- In another condition, he opened his mouth.

The results surprised many people who believed newborns were passive, socially unresponsive creatures: In the 20 seconds following each presentation, babies were more likely to match the action they had just watched (1983).

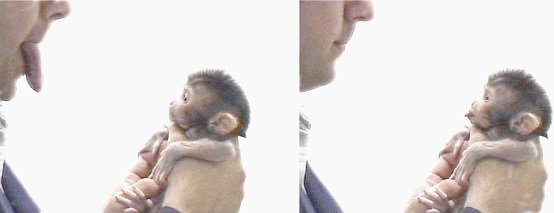

Subsequent studies have replicated the effect, even in nonhuman primates, like this newborn macaque (Gross 2006).

So it appears to be a response with deep evolutionary roots, though human babies have their own, special quirks. Unlike the monkey, our babies are more likely to mirror a “tongue out” expression when they are lying down or sitting in an infant seat (Nagy et al 2013).

Is this true imitation? Maybe not.

When Janine Oostenbroek and her colleagues revisited the phenomenon, they wanted to know if newborns are sticking their tongues out to match us, or doing it as a natural response to face-to-face communication. Maybe babies are just as likely to do it when we smile, or gesture with our hands.

The researchers ran their own matching experiments, adding new controls, and found they were right to be suspicious:

Newborns stuck their tongues out in response to several different displays, including happy faces and finger pointing gestures, and the babies didn’t appear to imitate anything (Oosterbroek et al 2016).

Still, it’s premature to conclude that newborns can’t mimic us at all.

In a series of experiments conducted by Emese Nagy and her colleagues (2014), 2-day-old infants were more likely to raise their index fingers after seeing their mothers do the same.

The newborns also mirrored gestures involving the movement of 2 fingers (making the “peace sign”). Moreover, they showed evidence of rapid learning, their gestures becoming more accurate with practice.

And all of these studies confirm a crucial developmental fact: Newborns are attentive and responsive to face-to-face communication, and ready to learn.

Indeed, Oosterbroek’s coauthor, Virginia Slaughter, thinks that babies may learn a great deal when we imitate them. She notes that parents mimic their infants very frequently, and this may provide babies with crucial opportunities to “link their gestures with those of another person” (Caputo 2016).

Are newborn babies capable of empathy?

If you’ve ever visited a newborn ward, you probably noticed that crying is contagious. One baby cries, and it seems to trigger a chain reaction.

Is it merely that babies cry in response to distressing noise? Apparently not. Research suggests that newborns can tell the difference between the sounds of

- their own cries;

- the cries of other newborns; and

- the cries of older babies;

and the contagious crying effect seems to be specific to hearing other newborns.

In one study, 1-day-old babies were more likely to cry when they heard an audio tape of another newborn in distress. But when they heard recordings of their own cries, or of the cries of an 11-month-old baby, the newborns didn’t respond (Martin and Clark 1987).

Is it merely a newborn reflex, a reaction that disappears after the first few days postpartum? Once again, it seems not. When researchers tested babies at months 1, 3, 6 and 9, they found that older babies, like newborns, responded with distress when they heard cries of pain (Geangu et al 2010).

As neuroscientists Jean Decety and Philip Jackson note, these studies suggest that young babies experience one of the basic ingredients of empathy — the ability to share the emotions of another person (Decety and Jackson 2004).

So what are the implications?

In times past, some people believed that newborns were effectively mindless: tiny survival machines that depended on us for food and shelter. But the studies cited here confirm that newborn babies are fundamentally social creatures. They seem designed to listen to speech, to seek out and differentiate faces, and to expect responsive social partners.

So perhaps the most important, practical lesson is to be on our guard against assumptions about the limitations of babies. If we take the position that newborns need little more than feeding and diaper changes, we may miss important opportunities to connect with them.

And while there’s still a lot we don’t understand about babies, the evidence supports a pro-mentalistic stance.

Studies suggest that babies develop stronger attachment relationships when we treat them like creatures with independent minds.

Science has also demonstrated the protective effects of positive, sensitive social interactions on a baby’s developing stress response system.

So if we have to err, let’s err on the side of attributing too much “mind” to our babies. We have little to lose, and who knows? Future studies might reveal that our generous attributions were right on target.

More information

To read more about the abilities of newborn babies, check out my articles, “The newborn senses: What can babies feel, see, hear, smell, and taste?” and “Newborn cognitive development: What are babies thinking and learning?”

In addition, you can read more about infant cognition in these Parenting Science articles:

“Moral sense: Babies prefer underdogs and do-gooders”

“Can babies sense stress in others?”

References

Batki A, Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Connellan J and Ahluwalia J. 2000. Is there an innate gaze module? Evidence from human neonates. Infant Behavior and Development 23(2): 223-229.

Beauchemin M, González-Frankenberger B, Tremblay J, Vannasing P, Martínez-Montes E, Belin P, Béland R, Francoeur D, Carceller AM, Wallois F, Lassonde M. 2011. Mother and stranger: an electrophysiological study of voice processing in newborns. Cereb Cortex. 21(8):1705-11

Bertin E and Striano T. 2006. The still-face response in newborn, 1.5-, and 3-month-old infants. Infant Behav Dev. 29(2):294-7.

Bushnell IWR, Sai F, and Mullin JT. 1989. Neonatal recognition of the mother’s face. British Journal of Developmental Psychology 7(1): 3–15.

Caputo J. 2016. That baby isn’t imitating you. Eurekalert, May 16 2016: http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2016-05/cp-tnb042816.php

Carpenter M, Nagell K, Tomasello M. 1998. Social cognition, joint attention, and communicative competence from 9 to 15 months of age. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 63(4):i-vi, 1-143.

Cooper RP and Aslin RN. 1990. Preference for infant-directed speech in the first month after birth. Child Dev. 61(5) 1584-95.

Cooper RP and Aslin RN. 1994. Developmental differences in infant attention to the spectral properties of infant-directed speech. Child Dev. 65(6):1663-77.

DeCasper AJ and Fifer WP. 1980. Of human bonding: newborns prefer their mothers’ voices. Science. 208(4448):1174-6.

Decety J and Jackson PL. 2004. The functional architecture of human empathy. Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Reviews 3(2): 71-100.

Dondi M, Simion F and Caltran, G. 1999. Can newborns discriminate between their own cry and the cry of another newborn infant? Developmental Psychology. 35:418–426.

Farroni T, Csibra G, Simion F, and Johnson MH. 2002. Eye contact detection in humans from birth. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99:9602-9605.

Farroni T, Pividori D, Simion F, Massaccesi S, and Johnson MH. 2004. Gaze following in newborns. Infancy 5: 39-60.

Farroni T, Menon E, Rigato S and Johnson MH. 2007. The perception of facial expressions in newborns. European Journal of Developmental Psychology 4(1): 2-13.

Geangu E, Benga O, Stahl D, Striano T. 2010. Contagious crying beyond the first days of life. Infant Behav Dev. 33(3):279-88.

Gross L. 2006. Evolution of Neonatal Imitation. PLoS Biol 4(9): e311.

Guellai B and Streri A. 2011. Cues for early social skills: direct gaze modulates newborns’ recognition of talking faces. PLoS One. 6(4):e18610.

Guellai B, Mersad K, Streri A. 2015. Suprasegmental information affects processing of talking faces at birth. Infant Behav Dev. 38:11-9.

Guellaï B, Hausberger M, Chopin A, Streri A. 2020. Premises of social cognition: Newborns are sensitive to a direct versus a faraway gaze. Sci Rep. 10(1):9796.

Hsu HC and Jeng SF. 2008. Two-month-olds’ attention and affective response to maternal still face: a comparison between term and preterm infants in Taiwan. Infant Behav Dev. 31(2):194-206.

Martin GB and Clark RD. 1987. Distress crying in neonates: Species and peer specificity. Developmental Psychology 18: 3-9.

Mehler J, Lambertz G, Juszyk PW, and Amiel-Tison C. 1986. Discrimination de la langue maternelle par le nouveau- né. Comptes rendus de l’Académie des sciences. Série 3, Sciences de la vie 303(15): 637-640.

Meltzoff AN and Moore MK. 1983. Newborn infants imitate adult facial gestures. Child Development 54: 702-709.

Nagy E, Pal A, and Orvos H. 2014. Learning to imitate individual finger movements by the human neonate. Dev Sci. 17(6):841-57.

Nagy E, Pilling K, Watt R, Pal A, Orvos H. 2017. Neonates’ responses to repeated exposure to a still face. PLoS One. 12(8):e0181688.

Nagy E, Pilling K, Orvos H, and Molnar P. 2013. Imitation of tongue protrusion in human neonates: specificity of the response in a large sample. Dev Psychol. 49(9):1628-38.

Nagy E. 2008. Innate intersubjectivity: newborns’ sensitivity to communication disturbance. Dev Psychol. 44(6):1779-84.

Oostenbroek J, Suddendorf T, Nielsen M, Redshaw J, Kennedy S, Davis J, Clark S, and Slaughter V. 2016. Comprehensive Longitudinal Study Challenges the Existence of Neonatal Imitation in Humans. Current Biology. Published online ahead of print. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2016.03.047.

Pascalis O, de Schonen S, Morton J, Deruelle C, and Fabre-Grenet M. 1994. Mothers face recognition by neonates: A replication and extention Infant Behavior and Development 18(1):79-85.

Rand K and Lahav A. 2014. Maternal sounds elicit lower heart rate in preterm newborns in the first month of life. Early Hum Dev. 90(10):679-83.

Tenenbaum EJ, Sobel DM, Sheinkopf SJ, Malle BF, Morgan JL. 2015. Attention to the mouth and gaze following in infancy predict language development. J Child Lang. 18:1-18.

Turati C, Simion F, Milani I, and Umiltà C. 2002. Newborns’ preference for faces: what is crucial? Dev Psychol. 38(6):875-82.

Uchida-Ota M, Arimitsu T, Tsuzuki D, Dan I, Ikeda K, Takahashi T, Minagawa Y. 2019. Maternal speech shapes the cerebral frontotemporal network in neonates: A hemodynamic functional connectivity study. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 39:100701

Vanderwert RE, Simpson EA, Paukner A, Suomi SJ, 2015. Fox NA, Ferrari PF. Early Social Experience Affects Neural Activity to Affiliative Facial Gestures in Newborn Nonhuman Primates. Dev Neurosci. 37(3):243-52.

Vouloumanos A, Hauser MD, Werker JF, Martin A. 2010. The tuning of human neonates’ preference for speech. Child Dev. 81(2):517-27.

Young GS, Merin N, Rogers SJ, and Ozonoff S. 2009. Gaze behavior and affect at 6 months: predicting clinical outcomes and language development in typically developing infants and infants at risk for autism. Dev Sci. 12(5):798-814.

Content last modified 8/9/2021

Portions of the text are taken from a previous version of this article written by the same author.

image of mother kissing newborn ©iStockphoto.com/Shawn Gearhart

image of newborn with mother and medical staff by US Navy

image of macaque © 2006 Public Library of Science.

image of infant with father by David Cox / US Navy