Pretending to be someone you’re not takes a toll on autistic girls

By Louise Kinross

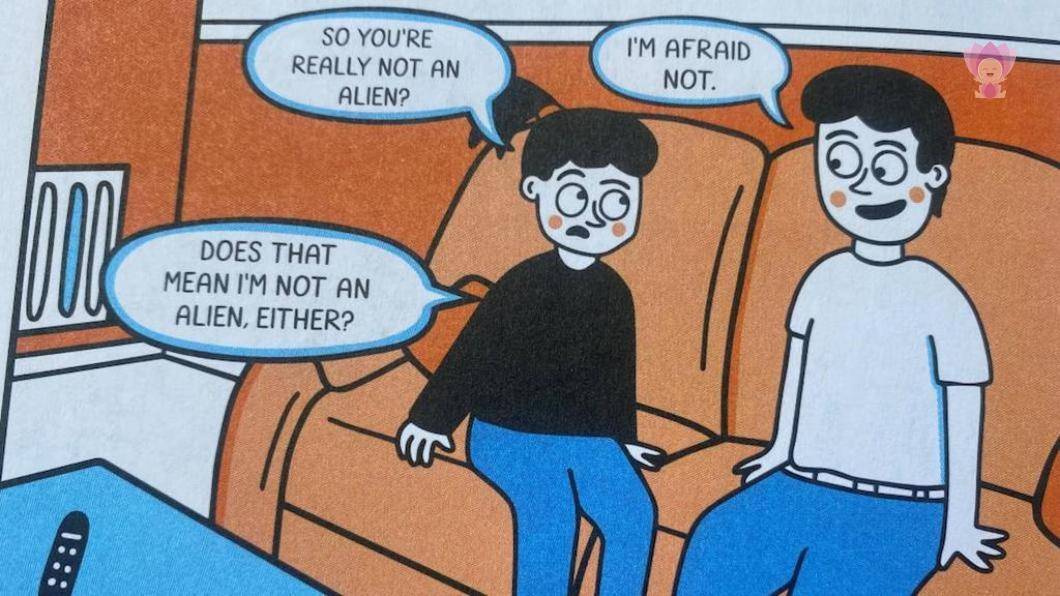

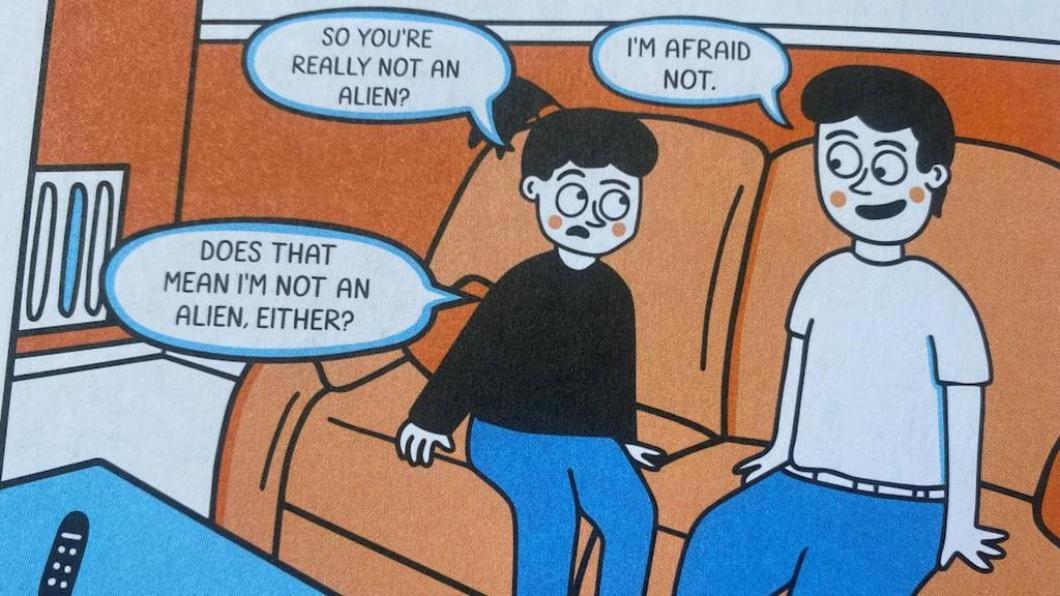

Frankie is an 11-year-old Irish girl who feels like an alien. She can’t stop talking and blurts out things at the wrong time, earning her the nickname “Freak” at school. “It feels like I’m speaking a different language,” she tells her mother. Frankie is the protagonist of Frankie’s World (image above), a stunning graphic novel for kids aged eight to 12. It’s written and illustrated by Irish comedian Aiofe Dooley, who was diagnosed with autism at the age of 27. Frankie’s World chronicles Aiofe’s childhood struggle to fit in.

I read Frankie’s World at the same time I was reading The Electricity of Every Living Thing. It’s a memoir by British author Katherine May, whose subsequent book Wintering became an international bestseller.

The Electricity of Every Living Thing is about Katherine’s 630-mile walk along England’s South West Coast Path. During the trek, sometimes compared to climbing Mount Everest four times, the 38-year-old discovers that she’s autistic.

Like Frankie, Katherine has always felt like an outsider. “I am unable to contain my thoughts as other people do,” she writes. “Everything always comes flooding out.” At school, “everything I did seemed to offend… I did everything I could to speak the same language as them, but I could see that it landed differently.” No one wanted to play with her. “I used to dream of being able to unpeel my skin to show that underneath I was just like them,” she writes. During her teen years, Katherine closely observed others so she could learn to “act normal.” But pretending to be someone she isn’t takes a toll: “It’s an endless miscommunication between the world and me; between me and the world.”

In Frankie’s World, creating an art project about her “true self” challenges Frankie because she’s used to hiding parts of her identity: her love of rock music (the other kids favour pop); frequent trips to the hospital because she’s underweight; and what she perceives as a misbehaving brain. She does have two close friends and finds humour in naming their trio “The Super Weirdos.”

Katherine doesn’t like to be touched. Frankie doesn’t like food items to touch each other on the plate. Katherine’s sense of alienation in the world intensifies after her son Bert is born. The sensation of him in a baby carrier against her body is disturbing. The sound of his cries can drive her to bang her head against the wall. “…I don’t seem to be like other mothers,” she notes. Certain social situations make her feel physically ill. “People carry electricity for me,” she writes. “They have a current that surges around my body until I’m exhausted.”

Frankie tries to “blend in” with her class so they don’t realize she’s “not normal.” She wonders if her dad, too, is an alien like her. He disappeared when she was a baby and she sets out on a quest to find him.

Desperate for time alone, Katherine spends a year walking along the southwest coast of England. She does the hike in stretches, often alone, sometimes with friends, and usually with her husband and son dropping her off and picking her up hours later. In the wilderness, “I am normal in my strangeness,” she writes. “Perhaps walking is the only place where I don’t have to pass.” Katherine ponders a radio interview she heard with an autistic person who reminds her, in some ways, of herself. By the end of her walk, she has taken three online tests to see if she fits the criteria for autism and learns she is “very likely” neurodiverse.

Frankie is able to track down her biological father and learns they have much in common, including autism.

“So… your brain’s broken?” she asks.

“The opposite, actually,” he says. “It’s like having a different operating system. It just works in another way!”

Learning about how her brain works helps Frankie understand and accept herself. Katherine, too, receives her formal diagnosis with relief. “Finally. I do have a life story that makes sense when you put it all together.”

The back of Frankie’s World includes a description of autism, facts and myths about the condition, and tips on being a good friend. Kirkus Reviews says: “Dooley, who is autistic herself, uses clean, comic-style art in black, blue, and orange. The illustrations are fun, playful, and endearing—just like Frankie. Frankie and her family are white; diversity in health, ability, and race is woven naturally into the story.”

Like this story? Sign up for our monthly BLOOM e-letter. You’ll get family stories and expert advice on raising children with disabilities; interviews with activists, clinicians and researchers; and disability news.

Leave a comment